This post introduces four British men who worked in the Victorian glass industry all their lives, each with their specialised skill. They were ordinary, and yet extraordinary – ordinary in terms of their glassmaking abilities, and yet extraordinary in the effect they had in a very far-off place. During a short period of work in Japan they gave instruction which transformed the country’s glassmaking, kick-starting today’s Japanese glass industry with its global reach. You can read a little of how this came about in the post below, but for a full appreciation of the topic, please read the attached downloadable PDF – the article I prepared in 2014 for the Journal of the Glass Association.

–0–0–0–0–0–0–

They went to larn ’em: four British glassmakers in early Meiji Japan

During the nineteenth century Britain was admired across the world for its industrial strength, and also envied. When far-away nations caught glimpses of items such as steam-powered machinery, powerful guns or mighty sea-going ships, they were captivated. The effect was so strong that some leaders stumbled over each other, politically speaking, trying to decide how to obtain such goods and enrich their countries by modernisation.

Pre-modern Japan

A classic and much-studied example of such technological growth is Japan. In the middle of the nineteenth century, when a formidable fleet of American ships burst in upon Japanese consciousness, Commander Matthew Perry dazzled a select group of people with a presentation of western goods the like of which most of them could have hardly imagined. He demonstrated, for instance, a miniature steam-powered train running on its own track, and the magic of sending a message by telegraph wires. At that time Japan had been almost entirely closed off from the rest of the world for over two hundred years under its self-imposed Sakoku policy and although the country was internally stable, self-sufficient, culturally sophisticated and highly structured, it was very different to the West. The economy was feudal and craftsmen such as glassmakers sold mostly luxury items on just a local scale. There was little awareness of the economic, social and cultural strides that the West had taken since the seventeenth century, and even less awareness of modern machinery, how it worked or what it could do for a nation.

The transformation of Japan

Perry’s goods made Japanese eyes pop. With their imaginations stirred, but not knowing how to set about the process of modernising their ancient country, leaders cast about among the western nations for allies who might be trusted to help. Within the small pool of European traders who had found a foothold in Japan by the time the new Meiji government was formed in 1868, was the British company Jardine Matheson, with its Scottish principal, Thomas Glover. An affinity quickly developed between Glover and Japanese leaders (in fact marking the starting point of a long Anglo-Japanese relationship which is still strong today) giving Japan the confidence to ask Britain to supply the men, machinery and knowledge their country needed. For their hearts and minds were set on bringing Japan into the circle of the world’s powerful nations.

Glassmaking

As the Meiji leaders learned more about western societies, they realised that amongst the things they needed were glass factories. Window glass, urgently required for all the new public and industrial buildings that were being erected, was costing the country dearly to import, and so the initial plan for their first glassworks was that it would make sheet glass. But this technology, like others that began to gather on their shopping list, was not at all easy to transfer far from its birthplace, and certainly not as easy as the Japanese imagined. Additionally, glass was needed for many other purposes – utilitarian glass, for industry, domestic lighting and tableware, ships’ signal lights, the chemist’s laboratory, and so on. Finally a decision was made, a site was chosen, and in 1874 the first attempts to make modern western-style industrial glass took place in a factory in Shinagawa on the southern edge of Tokyo, with many struggles. Over the next nine years, a total of four British glass craftsman instructed, advised and helped at the Shinagawa glassworks, one of them being my Scottish great-grandfather, James Speed.

The monument which was erected beside the site of the factory in 1965 states:

近代硝子工業発祥之地

此ノ地ハ本邦最初ノ洋式硝子工場興業社ノ跡デアル 同社ハ明治六年時ノ太政大臣三条実美ノ家令丹羽正庸等ノ発起ニヨリ我国ニ始メテ英国ノ最新技術機械施設等ヲ導入シ外人指導ノ下ニ広大ナ規模ト組織ニ依テ創立サレタモノデアル

然ルニ最初ハ技術至難ノタメ経営困難ニ陥リ同九年政府ノ買上ゲル所トナリ官営ノ品川硝子製作所トシテ事業ヲ再開シタ 同十七年ニハ再ビ民営ニ移サレ西村勝三其ノ衝ニ膺リ同廿一年品川硝子会社トシテ再興ノ機運ヲ迎ヘタガ収支償ハズ同二十六年マタマタ解散ノ已ムナキニ至ッタ

其ノ間育成サレタ技術者ハ東西ニ分布シテ夫々業ヲ拓キ斯業ノ開発ニ貢献シ本邦硝子興業今日ノ基礎原動力トナリ我国産業ノ興隆ニ寄与スル所頗ル大ナルモノガアッタ

吾等ハ其ノ業績ノ偉大ナルヲ偲ビ遺跡ノ保存ヲ図ッタガ會々此ノ挙ニ賛シタ 三共株式会社ハ進ンデ建設地ヲ無償提供サレタ 斯クテ有志ノ協賛ト相俟ッテ今茲ニ由緒アル発祥地ニ建碑先人ノ功ヲ不朽ニ伝フルヲ得タノデアル (昭和40年12月)Abbreviated translation:

Memorial for the birthplace of Japan’s modern glass industry

This place is the site of the first western-style glassworks named Kogyosha where Japanese glass manufacturing started in 1873. The factory imported modern British technology with foreign glass experts to instruct. When technical problems caused the business to fail, in 1876 it was nationalised and restarted as Shinagawa Glass Works. In 1884, it was privatised by Katsuzo Nishimura, and in 1888 restarted again as Shinagawa Glass Company. It finally closed in 1893 due to business difficulties. During these twenty years, many of the trainees spread out across all parts of Japan, initiating the country’s glass industry. It was a great contribution not only to modern glass manufacturing but also to Japanese industry.

James Speed

It was always said in my family that my great-grandfather, had ‘gone [to Japan] to larn ’em’, but growing up I never knew quite what that meant. In fact, for want of concrete information from my family and better geographical knowledge, I settled the matter in my young mind with the romantic notion that James Speed had been a teacher in some missionary school or other, far away in the mists of the far-away East.

It wasn’t until 2005 when my brother and I began to unpack this and other tales about our ancestors, with their numerous involvements in industry, that the real story came to light. As you can read in a previous post , most of my father’s paternal ancestors worked in the glass industry, but apparently his maternal grandfather was also a glassmaker. James Speed (1834-1908) had had the honour of teaching at a model glass factory set up with British help in Shinagawa, Tokyo, along with three other men from the British glass industry.

The three other British glassmakers

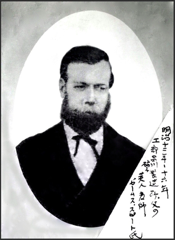

In a later post, James Speed’s life story will be recounted, as will those of the three other British glassmakers. They gave instruction at Shinagawa in various capacities between 1874 and 1883, as follows. Thomas Walton (1833-1897), a glass manufacturer, arrived first and oversaw the establishment of the first two furnaces. Elijah Skidmore (1836-1886) taught crucible making, while James Speed’s expertise was in various types of glassmaking, as well as management. The last to arrive was Emanuel Hauptmann (1848-1924), a Bohemian-born glass engraver and British national, who taught western-style glass-cutting and engraving.

Some parts of Hauptmann’s story are already known in Japan; if you type any combination of the words ‘Emanuel Hauptmann Japan kiriko glass’ into Google, you will find numerous short accounts of him in relation to Japanese kiriko glass. (‘Kiriko’ means facet or cut. Kiriko glass is fine cut crystal glass.) In modern times, Hauptmann’s work in Japan has captured the imagination of the contemporary Japanese glass world because of the effect his instruction had on the decorative techniques of Japanese glass.

This year, in search of a deeper story, and with the help of some of his descendants and various Japanese glass historians and craftsmen, I took a close look at the man and the legend, and wrote an article. You can read ‘Emanuel Hauptmann: the Father of Japanese Cut Glass’, published for the first time, in the next post. It is available in both English and Japanese translation.

If you would like to learn more about the four British men and the Shinagawa glassworks, please see this attached downloadable PDF:

–0–0–0–0–0–0–

This website honours the lives and work of all our ancestors who made things that were beautiful or useful, whether by craft or manufacture. Who Made That Glass invites you to learn about more of these people here, and to get in touch if you have any questions or similar stories you would like to share.